The Haunting (of) Richie Culver

Essay Commission for Solo Exhibition, Humber Street Gallery, October 2024

I. I was born by the sea / I was raised by the water / English seaside towns in January / it was normal / I knew I had to getaway / lighthouses flashing / oil rigs sparkle in the distance / it was normal / I knew I had to getaway / so I did / and I never looked back (Lyrics from I’ was born by the sea’ by Richie Culver)

Richie Culver recounted to me one recent afternoon that he has no intention of re-hashing the past, no impulse to lean on the same narratives repeatedly. What I hear is Culver expressing an internal process that has been ruminating for years, that is, new found space in his being for externalising to the world his artistic practice. I sense a willingness to explore and share shadow parts of himself through his work in a generous but considered way. This exhibition at Humber Street Gallery brings together for the first time, in a comprehensive display, parts of his practice that many will not have been aware of and certainly many have not seen before. After years as an outsider artist, Culver is stepping out of the penumbra. As Ursula Le Guin once wrote, referencing the influence of C.G. Jung on her own practice: ‘our job is growing up to become ourselves […] We need knowledge; we need self-knowledge. We need to see ourselves and the shadows we cast.’

My experience of Richie is of a person who is also highly attuned to his shadow parts, his other lives, his history and hometown, the ways his memories and experiences have shaped and continue to inform his multidisciplinary practice today. There is a quiet confidence in the way he recounts anecdotes to me, alongside a brutal honesty that is disquieting too: his Northern cadence transmitting through an almost dead-pan tone of voice places everything on the same level. Nothing is reified, yet everything potential material. His readiness to excavate from the deeply personal and the profane, the fringes and the ‘mainstream’ makes Culver’s practice hard to decipher at times, but all the more intriguing.

This essay will attempt to map the last two decades of Culver’s work, to investigate a practice that consistently and irreverently code-switches, reinvents and resists categorisation. As such, it will be unsuccessful in offering any linearity or chronology. Culver does not live in the past; he has come to terms with much of his own history. However, as Jacques Derrida suggests in his seminal 1993 text, Spectres of Marx, where the neologism hantologie (hauntology) appears for the first time, the past continues to haunt us, irrespective of its passing or perceived ‘death’. What is a shadow but a haunting of sorts? The question might be instead how do we meet our ghosts, be it on an individual or collective level? While Derrida’s work is situated in the post-1989 world, the collapse of the Soviet Union and European communism, hauntology as a framework still affords for a productive way to think through the ‘dislocated and dislodged,’ and the competing temporalities of contemporary life right now. If apparitions of the past continues to appear, or perhaps even more accurately, continue to travel along with us, what effect does this have on the mood and mode of the present? In what ways do they resonate and how are we able to attend to these ghosts?

Writer, music critic and teacher Mark Fisher expanded upon the concept of hauntology by applying it to electronic music emerging in the UK in the early years of the millennium. He described London artist Burial’s 2006 self-titled debut album as ‘suggesting a city haunted not only by the past but by lost futures… Burial is haunted by what once was, what could have been, and—most keeningly—what could still happen.’ Hauntological music is ‘more than a question of atmospherics’ for Fisher, they are sounds of a cultural grieving, the rhythms of industrial decay, late stage capitalism, abandoned dreams, the ‘ghosts of raves past.’ Culver grew up around raves, free parties and other nocturnal activities, in the warehouses and trap houses of Hull. One of his first encounters with art was at a rave in the mid-nineties where he stumbled upon a Nan Goldin book. He described to me as having an epiphany of sorts, realising that he could create art, even if he was ‘always starting from zero’ and ‘coming at things from the back foot.’

It is from these critical perspectives that I investigate Culver’s practice and work. My reasoning for this hauntological framework is three-fold. Firstly, over the last few years of friendship with Richie, I have observed his ability to harness and render the dislocated, disturbed and distorted, whether that is in terms of a cultural, collective or personal memory as material or in terms of how he translates the aesthetics of such experiences to create powerful, deeply affective work. Then, the conceptual implications of hauntology being given a ‘second (un)life’ in the realm of music feels pertinent, echoing Culver’s own journey as a self-taught artist, music producer/DJ and noise-maker. Thirdly, his practice teeters on the knife-edge of being quintessentially of its time and yet temporally ‘out-of-joint’ where the method and manner with which he has released work, made work visible (and invisible) is anachronistic, another defining characteristic of hauntology. We are living in a world marred with a cultural hegemony of a bean-counting scarcity complex, by time-stamping and living-for-likes, so there is plenty to mourn. For example, we could mourn a speculative future where indeterminacy could have reigned supreme: when we no longer count, measure and quantify as the primary defining framework for creating and producing, for being; when the process and the act of processing itself is the ambition, the path and the goal.

We might do this in the darkness of shadow-dancing, in therapy or by raving-to-live as my younger self would say or through what Culver does in his practice: utilising the integrity and productivity of the provisional. What I mean here is that creative acts to begin with are not finite objects in space-time, they are subjectivities that vibrate in the mind of their maker before they become discrete things in highly specific contexts, like art exhibitions or underground parties. Attuning to what serves when is a creative act too. Where the provisional-as-practice is immediately apparent in Culver’s artistic output is in his music, a place he is able to dive into the autobiographical. The personal and subjective are intimately connected to a method of the provisional, because it is the first lens we use to encounter the world and others. However, every modality of Culver’s oeuvre remains closely interwoven with one another and are therefore aspected by this provisionality too, even if they are material objects like sculptures or paintings. It is a question of transmission and filtering: Culver’s many artistic languages are not static, they are spectral.

II. No Fear / Mixed Feelings

With a DIY approach that includes painting, performance, sculpture and photography alongside the music he releases under the moniker Quiet Husband, Culver remixes academic rigour and ‘high art' with squat aesthetics, urban soundscapes and memes in iconoclastic gestures. Today, he navigates the underground music scene as much he does ‘art worlds,’ with recent shows and performances in London, Vienna and Berlin. Culver’s work creeps in and out of these different contexts like a phantom, never quite settling, disappearing and re-appearing in unexpected ways. This spectrality can be characterised by its ambiguity, liminality and at times, ephemerality. Ghosts are never fully present nor absent, they are neither dead nor alive. Where the haunted might seek solace or closure, the phantom offers instead the unresolved, the anachronic and often, the melancholic. However, there is potency in knowing what serves at the time being because it attends with greater awareness to the complexity of experience in the moment however long that might be.

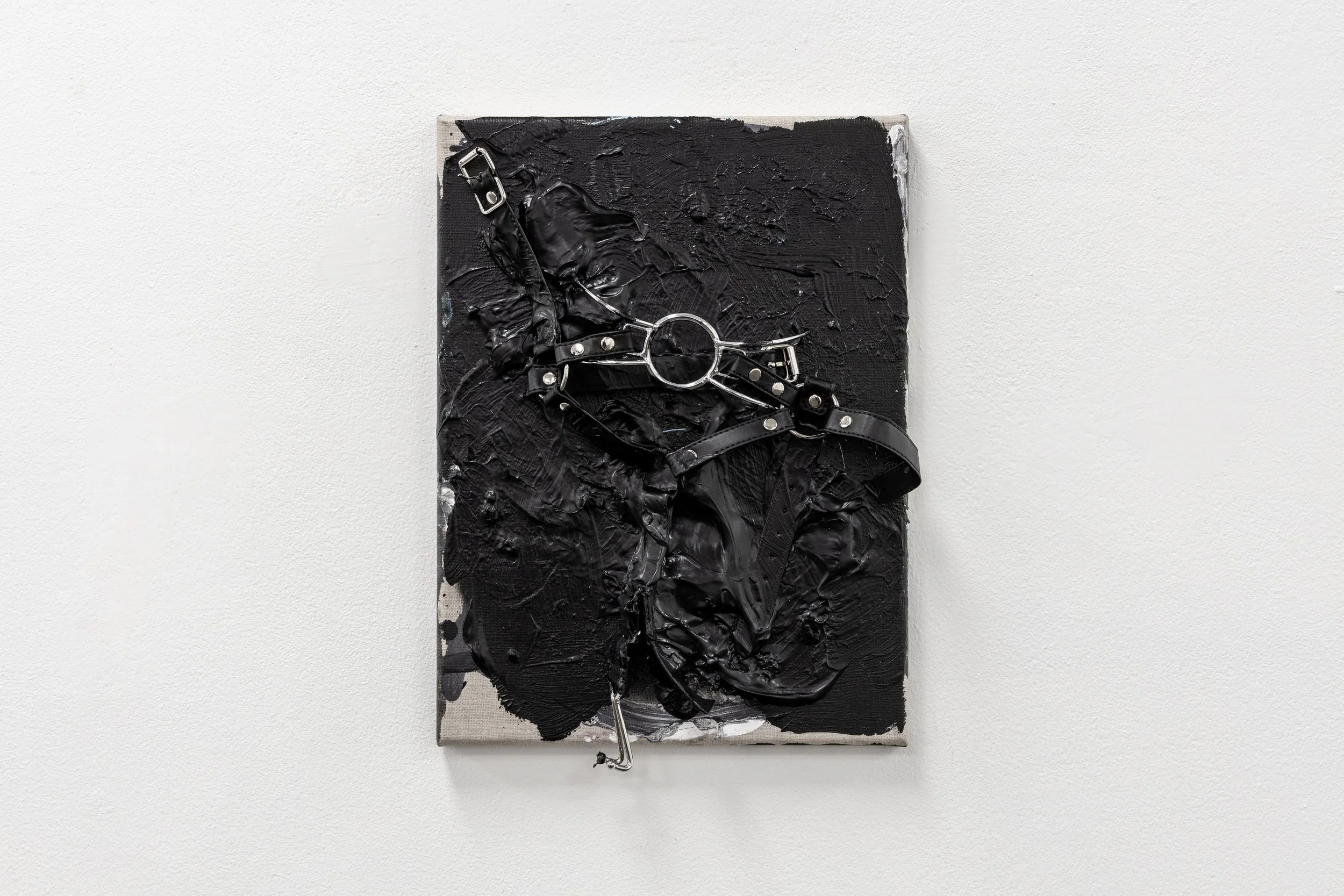

Some experiences, histories and memories are so complex that we find ways to cope by labelling, naming and analysing, this is good work for making sense of things. However, when dealing with such ghosts, a healthy dose of ambivalence might be productive too. Here, I do not mean a lukewarm creative direction or point of view (as Culver possesses these in spades) but rather how the being with mixed feelings might be a compelling method to tactically erode at structures and systems that prescribe or prohibit rather than liberate. For example, Culver has begun recent paintings with the Sports Direct No Fear logo where the process of painting compresses together the hand-drawn with acts of erasure and obscuration made of layers of white and black oil, ink and spray paint. Here, a number of competing ideas evoke different emotional responses: you could be looking at the exterior of a 1980s New York City subway from Style Wars, or an unintelligible tag scribbled on a derelict wall of a trap house, and an academic reference to the history of painting from Andy Warhol to Christopher Wool.

Untitled (2023) materially hints at the arcane in street-art as much as it hijacks the pop culture signifier of street wear. Despite graffiti often being perceived as a nuisance or a sign of ‘disorder’ in the urban metropolis, it is arguably simultaneously a secret language, legible only to a small group, and necessarily performed in ritualistic ways due to its illegality. Before ending up in London, Culver was working at a caravan factory and living in squats in his hometown where ‘strange ouija board messages and satanic’ tags defaced walls. Eventually, he found his way to Leeds where he held various jobs working on retail shop floors of Paul Smith, Vivian Westwood and Harvey Nichols. These were formative years: in the squats, he saw ‘heavy art everywhere in the graffiti’ and in the high-end fashion context, Culver took seriously the task of ‘curating the floor’ even making note of the ‘finger spaces between the hangers.’ These anecdotes speak not only to a hybridity that translates materially across Culver’s mediums, but also a conscious embodied approach to the world that is non-hierarchal, diverse and at times, (self-)reflexively contradictory.

The code-switching between these various visual and cultural languages means that it is difficult to remain convinced of one, but then again, maybe that is the point? If the either/or mentality were to die, what might surface in its wake is a self-aware irony still being spooked by a time where lines were clearer, enemies were better known, pre-the post-truth era, when art was apparently cozily situated in the realm of ‘high culture.’ Thus, embodying and sitting in the middle of mixed emotions in fact carves greater space for the reality that there is no consensus reality, just as the future is no longer futuristic so to speak.

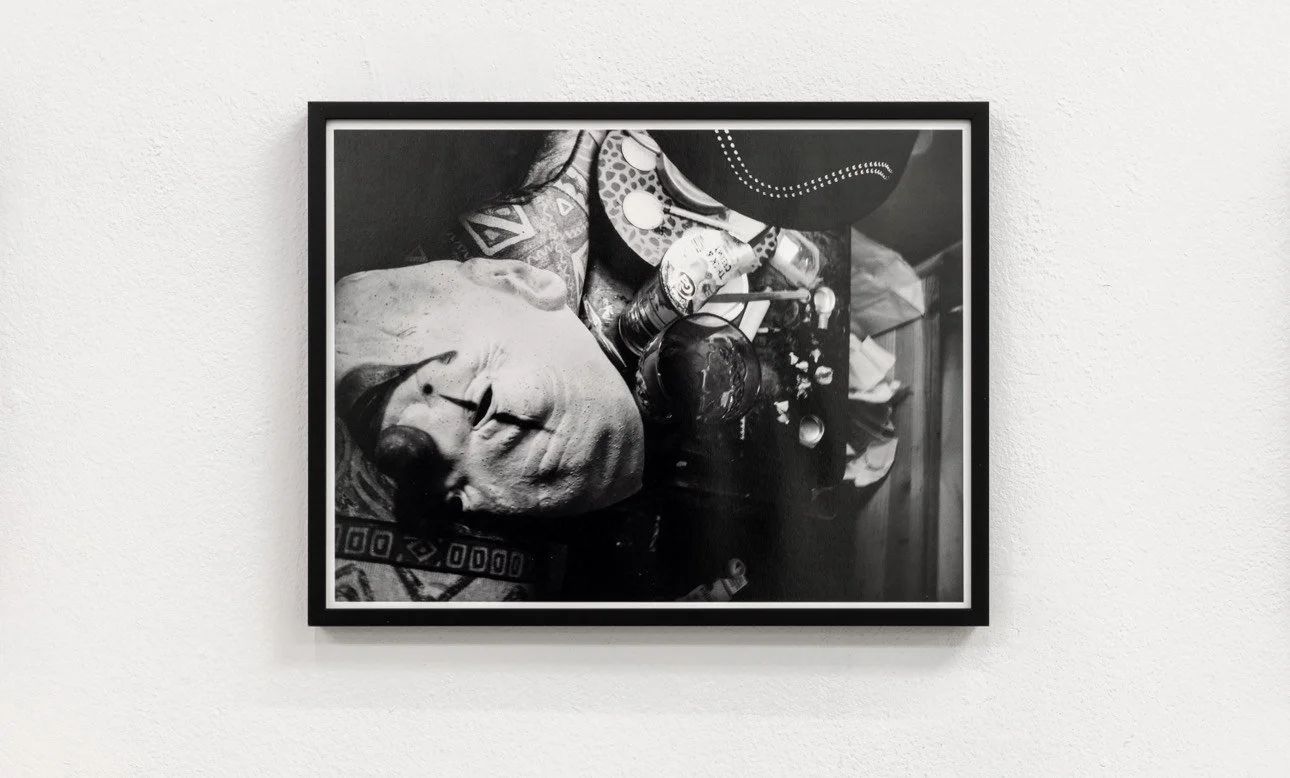

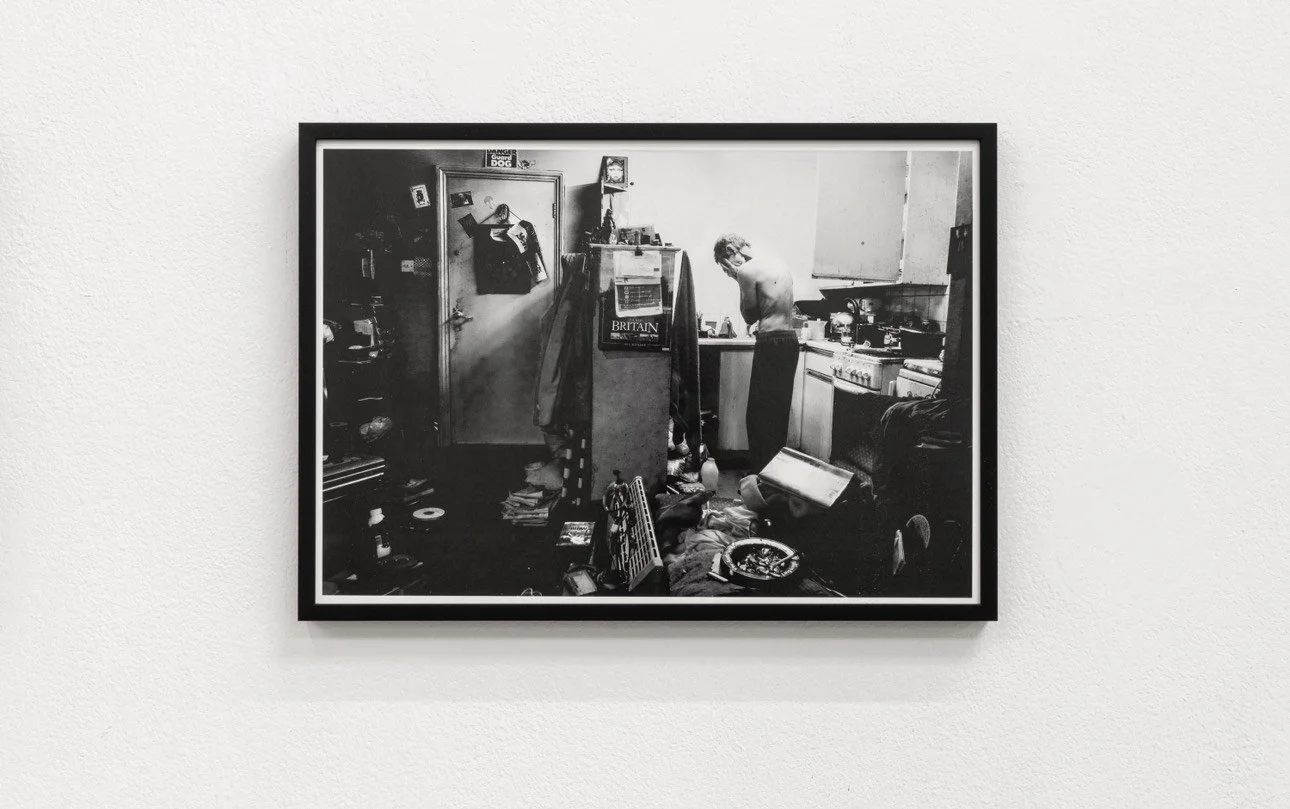

Culver knows what it means to be with mixed feelings. His visual practice makes similarly contradictory moves, just as he makes and moulds with dissonances in his music, experimenting with sonic extremities from the lovingly elegiac to the menacingly euphoric. The images captured between 2005-2009 presented in this exhibition are some of his earliest forays into the photographic medium. They capture daily scenes of intimacy, suffering, ecstasy and anxiety in the hidden context of a trap house: what was normal. Here, Culver takes on the role of an insider. After all, engaging with a spectre is a two-way street, an acting-back, a dialogue, much in the same way the experience of music is performed to and received by. You have to meet your ghosts to be able to discern their form, perhaps to release them too.

Collective ghosts continue to haunt us as much as individual ones do. In his Dis-figuration paintings, Culver explores how certain spectres haunt us communally. He recounted to me a childhood memory, a ‘core moment’ of visiting a war museum where a section was closed off to the public. Unable to enter, I imagine Richie sneaking a view of the galleries, encountering the medical work of Harold Delft Gillies, the father of modern plastic surgery, for the first time. The destruction and heavy artillery of World War I decimated an entire generation, a trauma that continues to affect humanity epigenetically. Inspired by album covers selected by noise artists featuring serial killers and other infamous persons, Culver re-imagines the stark, scientific photographs of men mangled by war and rehabilitated by Gillies’s pioneering skin-grafting method, albeit permanently deformed by their injuries. These paintings are not for the faint-hearted, they are deeply unsettling. As a viewer, you are asked to face, quite literally, the visceral wounds of ghosts past. These paintings act in a similar way that hardcore pure static noise does; one difficult to listen to, the other difficult to look at. Both probe shadow sides of humanity in their respective sensorial realms, creating feelings of discomfort and unease. Culver’s invitation is whether we can move deeper behind the veil and sit with the difficult emotions that arise when we ‘find the textures and give it a chance.’

III. Scream if You Don’t Exist

An arrhythmic, catchy beat pulses from my speakers whilst a high-pitched distorted voice screeches out ‘scream if you don’t exist’: my attention captivated. When I asked Richie where that turn-of-phrase came from, the title of his second LP, he responded that it was something he had ‘sat on for years and it felt like the right time to use it.’ Much like the logged memory of H. D. Gillies’ surgical work on war veterans re-appearing in recent paintings, Culver’s ability to mine from deep within his psyche, patiently waiting for the specific moment to make visible a creative act—be it a song, a painting or a T-shirt design—conjures the anachronic movements of apparitions, materialising seemingly at random but with purpose. The soundscape of Scream if You Don’t Exist captures a mood distinct to Culver’s artistry: unapologetic rawness deftly toned with sardonic humour and a free-hand spray of existential dread. Then again, engaging with phantoms means a willingness to grieve and to forgive as much as it is a process towards hope and potential new life.

Culver’s practice embodies the spectral through numerous artistic methodologies of the provisional—whether that is making space for the (un)reality of what it means to be human right now, holding it all together, barely and courageously, or breaking it all down, deconstructing the sacred and the profane. Temporality is not linear, no one medium is privileged over another, no experience or memory is untouchable. Ultimately, it does not matter the year the paintings were made, when the album dropped, nor when that collaboration launched. What matters is what is said, how it is uttered, spoken, shared and exhaled out into the world, in the broadest sense. These are the phantoms of a life examined, under examination now, and of an artistic practice that fearlessly dis-orients, interrupts and disrupts. Make no mistake, we are being haunted by Richie Culver.

Bianca Chu

Bibliography and Research Sources

Davis, Colin. 2005. ‘Hauntology, spectres and phantoms,’ French Studies, Vol. 59, 3: 373–379. https://doi.org/10.1093/fs/kni143.

Derrida, Jacques. (1994) 2006. Spectres of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International. London and New York: Routledge.

Fisher, Mark. 2012. ‘What is Hauntology?’ Film Quarterly. Vol. 66, no. 1: 16-24. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/fq.2012.66.1.16

Fisher, Mark. 2014 (2022). Ghosts of My Life, Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures. Hampshire: Zero Books. https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=uw6NAwAAQBAJ&pg=GBS.PT127&hl=en Accessed on 26 Aug 2024.

Fukuyama, Francis. 1989. “The End of History?” The National Interest, 16: 3–18. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24027184.

Graham, Stephen. 2016. Sounds of the Underground: A Cultural, Political and Aesthetic Mapping of Underground and Fringe Music. University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.8295270

Le Guin, Ursula. 2024. ‘The Child and the Shadow,’ in The Language of the Night. New York: Scribner, Simon & Schuster.

Postone, Moishe. Review of Deconstruction as Social Critique: Derrida on Marx and the New World Order, by Jacques Derrida and Peggy Kamuf. History and Theory. 37, no. 3 (1998): 370–87. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2505491.

Schacter, Rafael. 2008. ‘An Ethnography of Iconoclash: An Investigation into the Production, Consumption and Destruction of Street-art in London,’ Journal of Material Culture, 13(1): 35-61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183507086217

Van Elferen, I. 2011. ‘East German Goth and the Spectres of Marx,’ Popular Music, 30(1), 89-103. DOI:10.1017/S0261143010000693